|

VICTORIAN MOURNING

In some ways, this is a

book about death, or the obsession with death that permeated Victorian

society. It was a strange mix of sentimentality, morbid fear and snobbery.

Above all, it was about shopping. The Mourning Emporium of the title is a

kind of department store. It advertises itself like this:

|

|

|

Here is an extract from the

book that shows what Teo and Renzo see when they are first taken inside

the Mansion Dolorous by the London street children who have befriended

them:

'What the bucket ... !' exclaimed Teo, and then she too was silenced by

the prospect that began to emerge in front of them as the Londoners darted

about like fireflies, lighting ornamented gas-lamps.

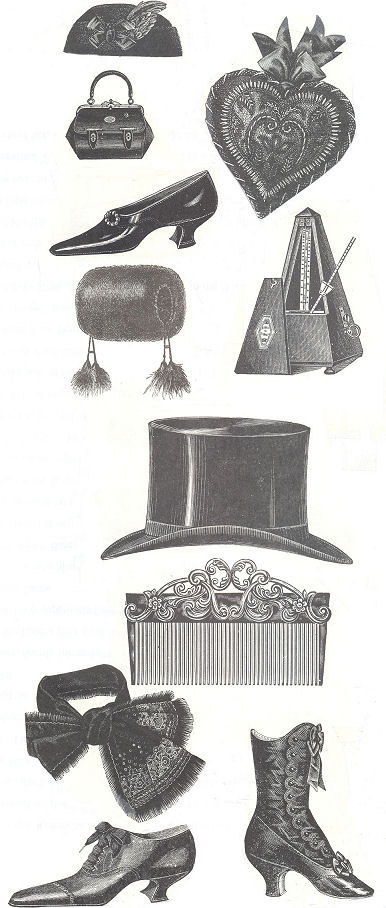

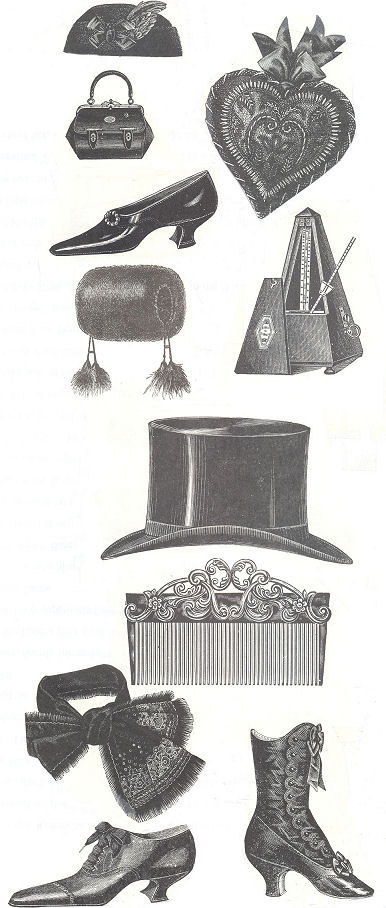

'A warehouse full of mourning vestments' did not

even begin to describe this Aladdin's Cave of jet-black merchandise. The

walls of the Mansion Dolorous were divided into towering caverns warmed by

glowing grates at regular intervals. Racks of dresses stretched into the

distance until they congealed into a slew of blackness. There were solidly

packed shelves of black-edged stationery, visiting cards and envelopes.

Teo glimpsed a card that read, 'You are desired to accompany the corpse of

'' with a blank left for a name. There were perfume bottles bedecked with

black ribbons. Black gloves were neatly folded on trolleys next to rolls

of black braiding trimmed with beads and sequins, black fringes, silk and

jet drops. There were crisply pleated silk mourning fans mounted on

ebonized sticks, black feather boas coiled in rustling black nests, and

white mourning handkerchiefs embroidered with black teardrops. There were

mourning cockades for coachmen's hats. An immense haberdashery cupboard

was honeycombed with compartments for black hairpins, black rosettes and

black armbands.

Mourning jewellery winked sombrely from

glass-topped cases. Renzo and Teo bent over a display of brooches made of

human hair plaited and shaped into patterns and set behind glass. Other

brooches showed dim daguerreotypes of sad faces. There were gold mourning

rings inset with black enamel, grey and black pearls, shiny jet bracelets,

scarf pins, tiaras, jewelled and feathered hair combs, lockets, pendants

and cameos with white profiles etched on onyx backgrounds. There were

mourning lampshades in Chinese pongee silk and mourning bookmarks

embroidered with forget-me-nots and doleful poems. There were black

funeral teapots and associated teaplates, and even a mourning ear trumpet

in vulcanite, horribly reminiscent of a black bat. And immortal wreaths of

flowers fashioned from Parian and silk, stiff and white under glass domes.

'How the English love death!' marvelled Teo.

'They seem to enjoy dying more than living. They must spend more money on

it anyway.'

'You haint wrong,' affirmed Hyrum Hoxton. 'And

this haint even the biggest mournin' emporium in London Town. You should

see Jay's in Regent Street. They is our deadly rivals. We hates em loik

poison.'

|

|

Tristesse & Ganorus's Mansion Dolorous Mourning Emporium is invented, but

it is very like two London magasins de deuil or mourning

warehouses. Jay's London General Mourning Warehouse opened at 248-9 Regent

Street in 1841. Peter Robinson's Court and General Mourning Warehouse in

Regent Street was founded in the 1850s. Even Harrods had a large mourning

department, including coffins, gravestones and every possible item of

mourning fashion. Dottridge's in the East Road was the wholesaler for all

funeral supplies. There, the coffins were made, the marble tombstones

carved and funeral carriages constructed.

Jay's

published its own heavily illustrated book by Richard Davey. A History

of Mourning describes the warehouse as a place where 'people in the

haste of grief can obtain in a few hours all that the etiquette of

civilization requires for mourning'.

That

'all', as this story shows, was a considerable amount.

People

desired a good funeral as a sign of their social station. Even very poor

people would subscribe to funeral funds, also known as burial funds, to

have the comfort of knowing that they would have a respectable

'sending-off' and not a shameful pauper's funeral. There was a widespread

belief in the profitable superstition that a brand-new mourning dress

should be bought for each death.

The

rules of mourning were strictly observed in society. Briefly, a widow was

expected to wear mourning for two years; the mother of a dead child, or a

bereaved child, twelve months. A dead sibling required six months'

mourning. But the etiquette and society magazines argued obsessively about

the minor details of even these matters.

The

high point of extravagant funerals was probably in the 1850s. The Duke of

Wellington's spectacular funeral was the last word in splendour, and

provoked something of a backlash. By the time of this story, the

Victorians had begun to praise more modest arrangements and accoutrements,

and to relax some of the more absurd refinements.

Church attendance was particularly heavy all over

the kingdom. The Sunday sermons openly spoke of the great loss that was to

befall the nation. The Times reported a sense of impending sadness from

Calcutta to Cape Town. The New York Times headlined with: QUEEN VICTORIA

AT DEATH'S DOOR '

The very stones of London seemed to

quiver with unspent tears and ancient frights; the river drew back from

its banks in an unprecedented low tide, like a bared grin of terror. Some

of London's long-suppressed ghosts began to grow more substantial, though

still weak and uncertain of their own existence. They emerged from their

hiding places and flitted about Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, almost

indistinguishable from the mist.

|

|

|

But

naturally, Queen Victoria's death provoked a final run on the mourning

emporia. On the days following her funeral, many people wore black. On the

day of the funeral itself it was hard to see anyone not dressed in weeds

among the crowds in London and Windsor. Queen Victoria herself, however,

had specified funeral decorations in purple and white.

|

|

|

At the end of the meal, Sibella produced a small,beautifully accurate black bear with button eyes and a dear little paunch.

‘Pray what is that?’ asked Mr Ganorus.

‘A Mourning Bear,’ replied Sibella.

‘A toy bear? It’ll never take on,’ frowned Mr Tristesse. ‘What child in its right mind would want to hug a bear and take it to bed?’ |

|